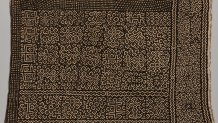

From haute couture to throw pillows, mud cloth, or bogolanfini, is woven into nearly every aspect of contemporary life. But what is the origin of this elaborate dye-decorated cloth? Bamana Mud Cloth: From Mali to the World, an exhibition on view at the Dallas Museum of Art through December 4, explains the process of the cloth’s creation and traces the cultural significance of its designs.

The exhibition features the museum’s recently acquired textiles created by the Bamana peoples of Mali. “Mud cloth is the translation of the word the Bamana use to describe this cloth: bogolanfini,” said Dr. Roslyn A. Walker, the museum’s Senior Curator of the Arts of Africa, the Americas, and the Pacific and The Margaret McDermott Curator of African Art.

Creating the cloth is a labor-intensive process. “A woman doesn’t get up in the morning and say, ‘I’m going to make a bogolanfini cloth today.’ She had to start thinking about this the year before because the mud which is used to make the dye had to be harvested from a river or pond and then it has to ferment with some herbs and spices in there to make it work,” Walker said.

Men weave locally grown cotton into strips that are sewn together. The cloth is dyed with a solution of pounded leaves and bark. After drying in the sun, the cloth turns yellow. The artists, traditionally women, use the fermented mud dye to decorate the cloth.

Get DFW local news, weather forecasts and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC DFW newsletters.

The artists divide the cloth into three to five sections and create designs for each section. A dark background is created around the designs by alternately applying mud, drying, and washing the cloth over time. “The design is determined by the person who is going to own and wear the wrapper,” Walker said.

Men who are hunters or warriors wear tunics with designs reflecting protection. Women wear bogolanfini wrappers for important milestones in life: coming of age, consummation of marriage, childbirth, and burial.

Local

The latest news from around North Texas.

The designs are rooted in Bamana daily life, myth, history, and philosophy. A peanut shell represents family unity and communal problem-solving. A lizard’s head signifies healing, wealth, and femininity. Small dots represent little stars. An interactive display in the exhibition allows patrons to create their own bogolanfini design using some of the Bamana people’s motifs.

While most of the cloths featured in the exhibition were made in rural areas, bogolanfini is now part of the urban culture. “In the modern world, cloths like this have been made by contemporary designers in Mali,” Walker said.

Chris Seydou, a native Malian designer who dressed many African first ladies, played an important role in exporting bogolanfini. “He ended up going to Paris and making a big splash in haute couture in the 1970s,” Walker said. “He was incorporating real African textiles in his designs and eventually, he focused on bogolanfini, focusing on specific designs and simplifying them.”

Contemporary designers around the world have been using bogolanfini motifs in their designs, rarely crediting the source of inspiration. “Norma Kamali really made the bogolanfini really popular in the United States in the 1980s,” Walker said.

Oscar de la Renta, Givenchy, Donna Karan and Ralph Lauren have incorporated the geometric designs into their collections. The motifs of bogolanfini are now popular in the world of home furnishings. Fixer Upper’s Joanna Gaines uses the patterns for throw pillows, upholstery, and rugs for the Waco-based Magnolia Home line. “They haven’t gone away. And they aren’t going away,” Walker said.

Walker often watches television with a camera ready to take pictures of bogolanfini designs in costumes and set designs, documenting how the patterns have seeped into the modern cultural landscape. “There are African fabrics that are part of lives. We take them for granted,” Walker said. “Especially from the 60s forward, we’ve really had African fabrics become part of what we sleep on and what we sit on.”