In Fort Worth, there is optimism about progress against the practice known as “redlining.”

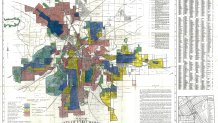

Maps were drawn by the US government-backed Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) in the 1930’s shaded red areas where lenders were discouraged from making loans. Those areas happened to be Black and Latino neighborhoods in cities including Dallas and Fort Worth.

The University of Richmond has posted the old maps online for cities across the US.

The obviously racist practice of redlining was outlawed years ago, but remnants of the lack of investment remain visible in many of the formerly redlined neighborhoods.

Retired Fort Worth Star-Telegram columnist Bob Ray Sanders has watched the effects in his city.

“The old thing was, you can't build a supermarket because Black people won't come. Or they'll come and they'll steal. And people won't invest in it,” he said.

The Dallas map has red shaded areas in a few areas near the center of the city. But the Fort Worth Map has many more red areas.

Sanders said the difference is because Fort Worth had smaller African American neighborhoods all around the city in the 1930s, on the east, west, north and south sides.

“So, when banks started drawing redlines around communities, they had to go almost all over the city of Fort Worth because that's where Black communities were. So, that's why you'll see a lot more red in Fort Worth than you would in Dallas,” Sanders said.

One area clearly in an old Fort Worth red zone is the Southside neighborhood along Evans Avenue at Rosedale east of I-35W. Several old churches still stand, but that’s about all that remains of what was once a thriving African American commercial street.

“You’ve got a lot of inadequate housing. You’ve got a lot of businesses gone. You’ve got a lot of vacant lots,” Sanders said.

Several older neighborhoods near the center of the city are in this condition while new homes and retail development thrive in booming Fort Worth areas far to the north and west.

Fort Worth native Devoyd (Dee) Jennings is the Fort Worth Black Chamber of Commerce President.

“You really get disappointed when you see large areas, like a quarter of the city that are not thriving,” he said.

The old neighborhoods are close to healthy downtown Fort Worth with access to major highways and public transportation.

“So, the development has to come here. It’s just, when,” Sanders said.

In an effort to promote redevelopment around Evans and Rosedale, the City of Fort Worth recently repaved streets and added new lighting. It has not yet attracted redevelopment on vacant land along those streets like what’s happening on the outskirts of the city.

“Those things have been neglected from those neighborhoods for decades. And just the last few years you're going to address those? Great that we're doing that, but what does this tell you about the disparities that have existed for decades in this city,” Sanders said.

A very different Fort Worth story is unfolding in another area a little farther to the southeast.

Not so long ago, the neighborhood around the former Masonic Children’s Home orphanage has no stores. More than 100,000 residents in that part of the city had to travel elsewhere to shop.

“What happened is that the Walmart store came in, and that drew the other stores, and then the development started happening,” Jennings said.

The city added new streets. And now, the area known as Renaissance Square has new apartments with new single-family homes planned.

“This is a success story, most definitely one of the greatest success stories in the history of Southeast Fort Worth. And it took a lot of people to do it,” Jennings said.

One of those people is resident Carl Pointer. He was involved in the fight to raise money from multiple sources to get a $16 million YMCA to relocate to the former orphanage site.

“It was really, really hard, to get this done,” Pointer said. “Raising money for a facility like this in Southeast Fort Worth was just unheard of.”

But it happened.

Other changes are now in the works for the Southeast side.

Two public housing projects are in various stages of redevelopment for new mixed-income housing. Community leaders are pushing to avoid gentrification that could keep people who live in those neighborhoods from being forced out by cost of living they can no longer afford.

“It's been better progress over the last 10 years than it was prior. And we think that the progress should keep going because Fort Worth is up and moving right now,” Jennings said.

Remarkably, the George Floyd protests of 2020 and the COVID-19 pandemic may be the influence that increases the chance of lasting change in these neighborhoods, according to Sanders.

“The whole system is full of disparities, and that's what it exposed. And suddenly you have banks, I mean national banks saying, we need to put more money into the Black Community. We need to figure out how we recuperate some of these communities that have been dying for decades.” Sanders said.

Jennings confirmed that lenders are starting to see that improving these neighborhoods can be good for bank business, as well.

“You’ve got to look at the upward mobility of creating an atmosphere that’s going to leave to something,” Jennings said. “When you look at that picture, it changes the whole dynamic of your city.

These veterans of a long fight say it may finally be harder in the near future to see where the old red lines were in Fort Worth.