Two art exhibitions honor the Indigenous people of North Texas.

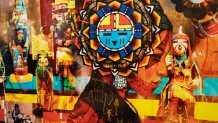

“Yahvlane & Ha Įlè - Art without Borders,” organized by AT&T Discovery District in Dallas and C2, an art advisory firm with offices in Dallas and Houston, acknowledges the Caddo, Wichita, and Kickapoo tribes as the original stewards of the land now called Dallas, Texas.

The exhibition features Ha Įlè, an augmented reality sculpture project by Texas artist Eric Wagliardo and First Nations interdisciplinary artist Casey Koyczan from Yellowknife, Canada. The project is sponsored by the Consulate General of Canada in Dallas and the City of Dallas Office of Arts and Culture, intended to further cross-border cultural dialogue.

Get DFW local news, weather forecasts and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC DFW newsletters.

The exhibition also prominently features the work of Brian Larney. The Dallas native is a Choctaw of Oklahoma and a citizen of the Seminole Nation. His tribal family name of five generations is Yahvlane, meaning Yellow Wolf in Seminole. He calls himself an urban American Indian.

“My concrete jungle is Dallas,” Larney said.

As Chair for the American Indian Heritage Day in Texas (AIHD), Larney is a representative of truth for American Indians.

Local

The latest news from around North Texas.

“You’re part of a community,” Larney said. “For me, I try to make sure to preserve the voice for the community, but as well as look through the lends of equity and equality to sure we’re represented in the best way.”

Larney works to dispel the myths Hollywood and biased historical narratives created about Indigenous people.

“I’m fighting under so many stereotypes,” Larney said. “Perception is not what you see face-to-face; it’s what you’ve been told through miscommunication or storytelling. It has always been marketing that’s always put us in a bad light until you meet us and then you find out everything is different.”

Through his illustrations and paintings, Larney explores racial identity, cultural struggles and the history and traditions of Chocotaw and Seminole nations.

“I don’t look at art as being pretty. For me, art is cultural wealth and cultural wealth, for me, is the parts where you dissect it, where it becomes cultural preservation,” Larney said. “It does talk about social issues. It does talk about historical value. It does talk about the roots of our people, but at the same time, art is, I always say, that it is my world interpreted. You walk into my world to see what our truth is, our historical value and it’s also an educational piece.”

The history of American Indians in North Texas is brutal. Dallas’ official history begins with John Neely Bryan establishing a permanent settlement in 1841. Bryan and General Edward Tarrant removed and massacred the Caddo Indians living along the Trinity River before dividing and selling the land.

“You don’t define massacres. You only define who is here,” Larney said. “It is tough when Founders Plaza has no American Indian entity of anything on that plaza, but then you find out that the cabin is actually a structure from the Chocktaw nation, but the migrants are called settlers from Tennessee.”

Many Texans do not know the origin of the state’s name.

“They think the word is Mexican for the dialect for the naming of the state when it is actually Caddo. A lot of people don’t even know it is a Caddo word,” Larney said.

In Fort Worth, “Speaking with Light” is part of the Carter’s reconsideration of how Indigenous people are depicted in art.

“’Speaking with Light’ was born out of our museum’s interest in reassessing our collection of more than 5,000 photographs depicting Indigenous people across what today is the United States. Recognizing that almost all of these photographs were made by Euro-Americans, our initial plan was to ask what it means to photograph as outsiders to the cultures one is depicting and to have the show’s last section flip the conversation by showing photographs created by Indigenous artists over recent decades. After consulting with Indigenous scholars across the country and recognizing the diversity and vitality of this contemporary work, we decided to refocus our attention,” said John Rohrbach, co-curator of “Speaking with Light” and Senior Curator of Photographs at the Carter.

The exhibition showcases the perspective of 574 federally recognized Indian nations along with the many tribes only recognized at state level and others who are still seeking recognition.

“Most importantly, the photographs and videos filling ‘Speaking with Light’ reflect insiders’ views of Indigenous cultures and sitters. Rather than one voice, the works come from many cultures and perspectives,” Rohrbach said. “To give a brief taste of those perspectives, consider what your outlook would be if you had to live far from your traditional homelands, where plants, animals, and even stones, are as animate and important as humans in defining your community. Now consider you are responsible not only to your present community and the achievements of your ancestors but to your offspring seven generations into the future—all while contemporary life for most means living surrounded by stereotyping that relegates you as part of the past.”

The exhibition features more than 75 photographs, videos, and sound piece from 30 artists representing more than 40 Indigenous nations. A prologue explains the Europeans and then the United States accepted Indigenous sovereignty. That relationship continues today.

“Just last week President Biden held a Tribal Nations Summit,” Rohrbach said.

The exhibition features more than 30 artists, 75 photographs, videos, three-dimensional works, and digital activations that forge an investigation into identity, resistance, and belonging.

Rohrbach explains how he and co-curator, Will Wilson, a citizen of the Navajo Nation, divided the exhibition into three sections.

“The show’s first main section, Survivance, a term coined by Anishinaabe scholar Gerald Vizenor, presents photographs and videos by Indigenous artists addressing issues of stereotype, deep connections to place, and living surrounded by a hostile culture. These artists share their frustrations, their anger, and their points of view in remarkably diverse, even entertaining ways.”

“Its second section, titled Nation, presents art works that reflect on what it means to be Indigenous across North America, probing one’s responsibilities to one’s community.”

“The third and final section, titled Indigenous Visualities, takes visitors even more directly into Indigenous worlds, sharing how artists are seeking to retain and trumpet deeply felt connections to specific places, to support their young people and elders, and to reflect on what it means to be Indigenous in the twenty-first century. The exhibition ends with recognition that many of the issues raised by the artists through the show are similar to those being addressed by Indigenous photographers across the world.”

Rohrbach points out the recent census data shows more than 60,000 citizens of the DFW area representing more than 200 Nations self-identified as American Indian.

“American history and identity are rooted in the attempted sweeping away of hundreds of Indigenous cultures by European and United States citizens. Some call it assimilation while others call it genocide. Certainly, it was often quite violent not only physically, but economically and psychologically. These scars remain very much alive for many Indigenous people today,” Rohrbach said.

Both exhibitions challenge visitors to reconsider the full scope of American history and culture.

“It is hard to understand American identity if we do not know our history. This exhibition provides one small step in helping people better understand Indigenous perspectives through some remarkably varied and engaging art works. The challenge is not to return to the past but to consider how we together might build a better world,” Rohrbach said.

“It’s a platform on which we share to make sure other people see the value of our culture,” Larney said. “This shouldn’t be a forced educational part. It should be a shared visual implementation or a beauty that we want to share who we are, we’re proud of who we are, we make sure our identity is pushed forward.”

Learn more: AT&T Discovery District and Amon Carter Museum of American Art