The family of a man who man died while in custody at the Collin County Jail continues to push for answers. Marvin Scott's family says when Allen Police arrested him, he was experiencing a mental health crisis.

According to the Arlington Police Department, one in 10 calls to the police is related to a mental health situation.

"It’s at a time where we’re looking at police to do more than just the enforcement side, to do more than just throw people into jail. I don’t think you can arrest your way out of social problems," said Lt. Kimberly Harris who oversees the Arlington Police Department Mental Health and Community Advocacy Unit. "Actually training officers to go into the situation looking at, 'What is the need here? And how can I fulfill that? What can I do to make their lives a little better?'"

She said every officer receives 40 hours of crisis intervention training. There are also officers specialized in a unit made up of behavioral health response officers. They will partner with clinicians from My Health My Resources through Tarrant County who ride along with officers at least twice a week.

Get DFW local news, weather forecasts and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC DFW newsletters.

“A lot of folks that we encounter are just sick and they’re having a really bad day and we need to be able to recognize their illness, what it is and treat them appropriately, get them the treatment that they need or refer them to the treatment that they need," said Trevor Clenney, mental health initiative officer for Arlington police.

He said his position was funded through a grant and he helps with strategic planning for the city's mental health initiatives.

During his 19 years with the force in Arlington, he said he would interact with people in the community and saw the need for behavioral health initiatives while patrolling the east district.

Local

The latest news from around North Texas.

“We would look to see if we could provide them with any types of resources or see how we could interact with them in the future, and we would respond to calls in the process where people were actively dealing with a crisis," Clenney said of his time in the field.

He said over the years he has seen the positives of having a clinician on hand.

“I was honestly a bit of a critic when I was on patrol whether or not I felt that I could intervene appropriately in situations like this, but as I saw the program work and I saw clinicians from our local mental health authority riding with people that I had worked with for years, I saw those calls deescalate very quickly," he said.

Harris said what the department has noticed over the years are repeated calls for the same individuals who many not to go to the hospital or are not committing a crime.

"So we needed a service that could step in and fill the void where it usually would be filled by police officers going out to the call," Harris said.

Filling in the G.A.P.P.

Arlington police say to help minimize repeat calls for the same individuals, they'e partnered up with a program called G.A.P.P.

The Greater Access and Partnership Program launched in 2019 and is part of a nonprofit called Alliance Child and Family Solutions.

"Basically we exist to help those who have been referred to law enforcement usually for mental health needs to get the resources and ongoing counseling that they need so that they can be stable and not continue to escalate to that point where it’s requiring police intervention," Alliance Child and Family Solutions CEO Anastasia Taylor said.

It started working with Arlington police last fall and is hoping to expand to other police departments in Tarrant County.

"We’re trying to assess for any needs that the individual may have and basically provide that ongoing support and mental health care so that individuals are stable, they’re symptoms are not escalating or increasing and we’re able to make a long term difference in their lives based on their physical needs and their emotional needs stabilized," Taylor said.

While police respond to the crisis at the moment, G.A.P.P. is there for the next step, to help the person with long term needs, including something like filling out applications to get service.

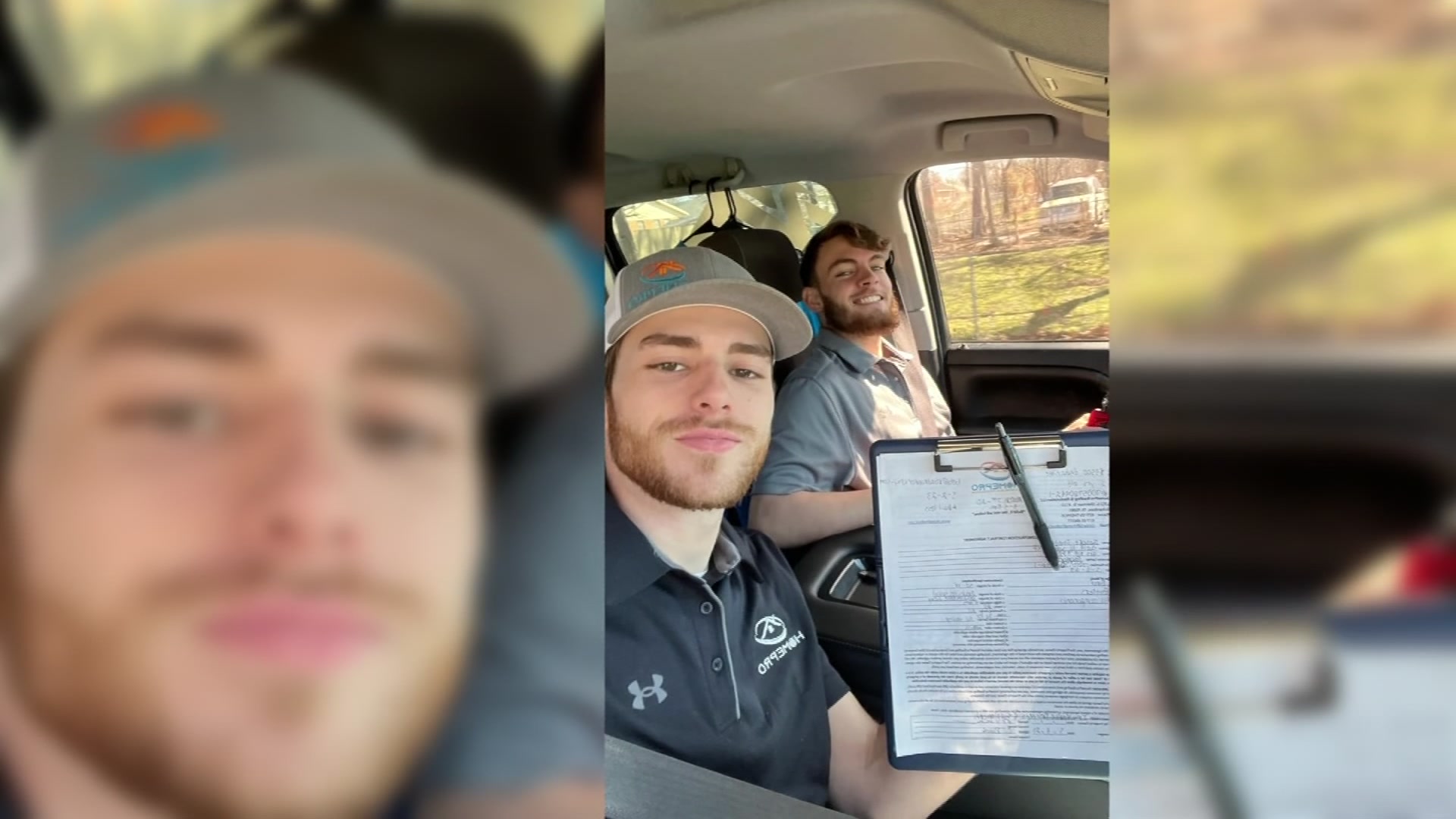

"We actually go out to the homes, sometimes, depending on the nature of the situation, if there’s a past history of violence, substance abuse or extreme mental health symptoms, an officer may be present for our first initial meeting," Taylor said. "Whether they’re needing food, shelter, transportation, medications, or ongoing care, we help make sure that they’re connected to all the resources they need and help work alongside the police department so that if concerns do arise, we’re able to help keep that from being a bigger situation.”

Clenney said there's a portal set up for officers to use to make referrals for people through the program.

“It’s very simple and takes less than five minutes and their goal is to follow up with them in 24 hours," Clenney said.

"I know in various studies there have been high numbers in which law enforcement has indicated that because of the increased rate of serious mental illness and lack of resources, now law enforcement resources and time are having to be diverted to mental health needs, rather than sending a mental health clinician," Taylor said.

The overall goal of having programs and clinicians to assist with behavioral crises is to reduce the number of involuntary hospitalizations or jail.

Harris said even though the department looks for ways to solve a situation, and uses resources, sometimes it can be challenging for officers who say a person may still be arrested due to a criminal act that took place.

"Sometimes we do have to take people to jail, however in order to prevent that repetitive behavior, we get them involved in services with G.A.P.P.," Harris said. "If we have to talk to them at the jail, we'll do that. If we have to a phone call after they've been in jail, we'll do that as well. Make the referral and get them linked up that way there's somebody they can call, somebody they can talk to."

Funding is also crucial to keeping social and behavioral health services afloat, and both police departments and nonprofits are in need of more money.

“The reality is Texas we’re underfunded. We’re 48 out of 50 in the United States so there are limited resources and that’s where a lot of these calls end up filtering to police officers," Taylor said.

"There are a lot of grants available, but everyone is rushing to get those grants and I know police departments and city departments are going to say they need more funding, and that would definitely be able to help," Harris said.