Update: With the continued spread of the omicron variant of COVID-19, we are republishing and updating the 2020 article below to highlight the differences between coronavirus and cedar fever.

It's that time of year again: Watery eyes, runny nose, and lots and lots of sneezing all thanks to "cedar fever."

Specifically, mountain cedar, which is also known as Ashe juniper. Mountain cedar season runs from late December to February, so, unfortunately, it's just getting started.

Health News

Get DFW local news, weather forecasts and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC DFW newsletters.

NBC 5 viewer Diane Smedley of Aledo shared the video above, where you can see the cloud of pollen erupt from the tree.

"Well I woke up sneezing this morning and as I was looking out the window at this old mature cedar tree, kept seeing these puffs of smoke," said Smedley. "I had no idea what it was, at first I thought it was fog, and then realized it's pollen!"

Put simply, cedar fever is an allergic reaction to cedar pollen in the air. Something allergy sufferers know too well.

Symptoms of cedar fever include sneezing, itchy, watery eyes, runny nose, sore throat and fatigue as well as aches and pains.

Those symptoms sound like coronavirus right?

While it doesn't actually cause fever, the inflammation and triggering of your immune system associated with allergies can raise your temperature, but not above 101° -- if you have a high fever, or you lose your sense of taste or smell, you should get tested for COVID-19.

Rain or a strong north wind can help in the battle against cedar pollen, as well as staying indoors and changing your air filters.

Over-the-counter antihistamines, nasal decongestants, and nasal sprays can also help.

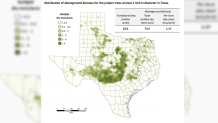

A map published by Texas A&M Forest Service shows where juniper trees are most prevalent. Clearly, the highest concentration is to the southwest of the Dallas-Fort Worth area.

"Cedar fever is the worst west of I-35, where you have primarily juniper mixed in with oaks and some other species," said Jonathan Motsinger, the Central Texas Operations Department Head for Texas A&M Forest Service. "And because all of those junipers are producing pollen at the same time, you're going to get a higher concentration of pollen in the air."

These trees typically begin producing pollen in mid-December, often triggered by colder weather or the passage of a Texas cold front. Pollen production reaches its peak in mid-January, before slowly tapering off toward the beginning of March, just in time for oak pollen and other spring allergens to start up.

“Immediately before and after a cold front it gets very dry and windy and the pressure changes very rapidly,” said Karl Flocke, a woodland ecologist for Texas A&M Forest Service. “This triggers the opening of pollen cones and the release of the pollen grains. When you see the pollen billowing off a tree that has just ‘popped,’ or opened its cones, it looks very similar to smoke coming from a wildfire.”