- As Americans resume pre-Covid activity and the White House seeks even more stimulus, President Joe Biden's policy agenda may be his biggest economic threat.

- "The headwind could be too much of a good thing," economist Allen Sinai says of continued stimulus efforts like Biden's infrastructure plan and the rising risk of inflation.

- Biden has a lot to celebrate about his economy: Job growth and wages are on the rise, economic activity is returning and the S&P 500 is breaking records.

- The Federal Reserve could move to hike interest rates if inflation spikes in the second half of 2021 or beyond.

Halfway through 2021, and about six months into the Biden administration, the U.S. economy has by many metrics made a full recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic.

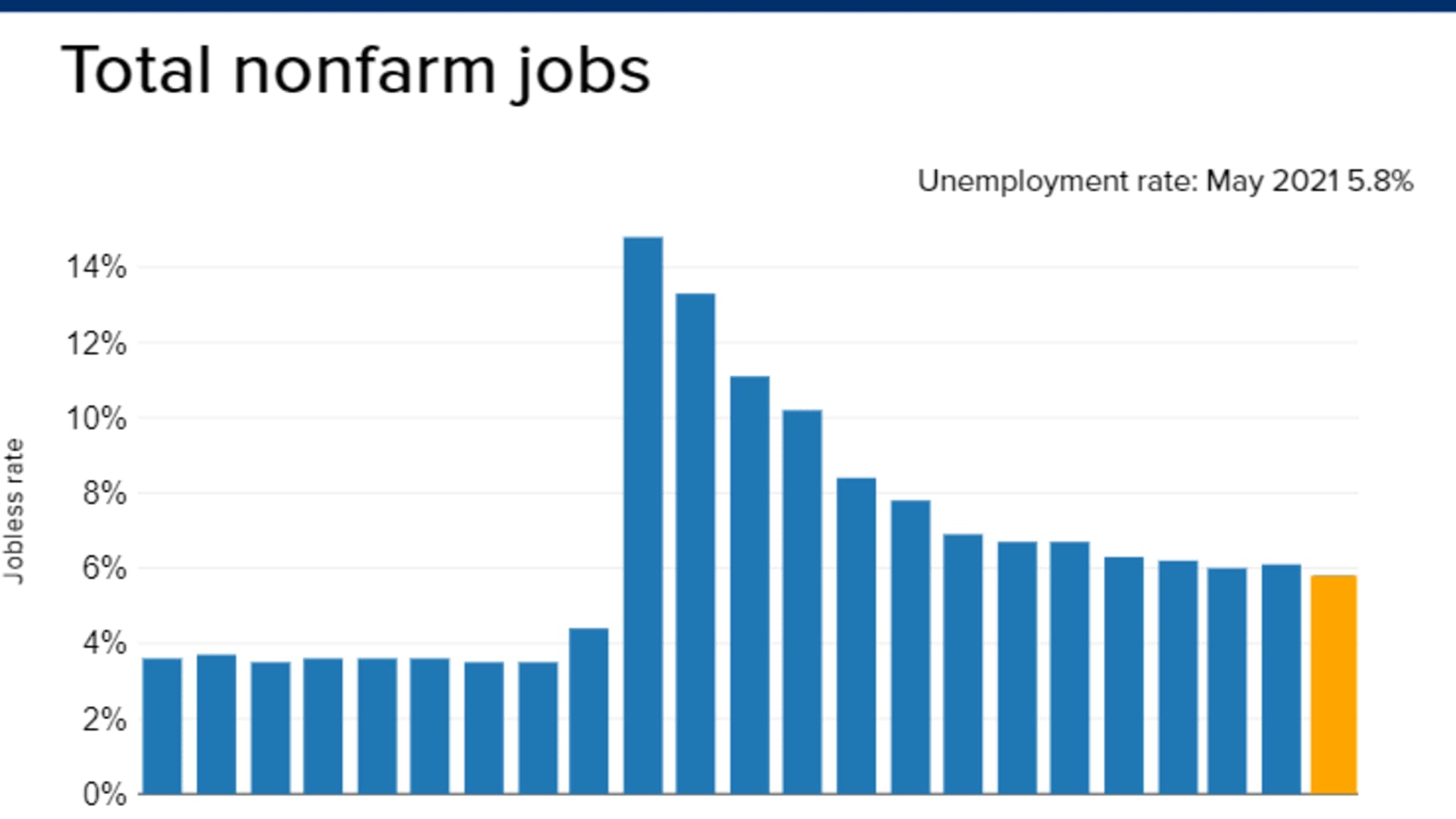

One year ago, nationwide business closures sent the unemployment rate climbing to 13.3%. It's now at 5.8%. Average hourly wages are now higher than they were just before the pandemic.

The stock market is at record highs, and U.S. consumers are now feeling more confident than at any point in the last 16 months. GDP, which swooned 31.4% in the second quarter of 2020, is expected to top 8% in the second quarter of 2021 and herald a new era of business expansion.

Get DFW local news, weather forecasts and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC DFW newsletters.

So with employment, wages and economic activity up, the S&P 500 reaching new highs, and effective coronavirus vaccines within reach of nearly all U.S. residents, what could possibly derail the Biden economy?

The answer to that question, according to some economists, is Biden himself.

As the president proposes trillions more spending on top of a historic level of stimulus, the risk is that his administration could overheat the U.S. economy and spark a wild spike in prices.

Money Report

As workers return to the labor force and American consumers rush to spend months of pent-up savings accrued during the pandemic, the risk of overheating is now the greatest hazard for the U.S. economy, said Allen Sinai, chief global economist and strategist at Decision Economics.

"The headwind could be too much of a good thing," Sinai said Tuesday.

Perhaps paradoxically, "the headwinds are a consequence of the tail winds," he continued. "In the rush to cushion and save the economy, was too much stimulus supplied?"

Having learned from the mistakes of the financial crisis more than 10 years ago, federal lawmakers and the Federal Reserve moved quickly in March 2020 to flush the economy with stimulus.

While Congress and former President Donald Trump worked to pass the $2.2 trillion CARES Act, the Fed slashed interest rates and embarked on a historic effort to flood financial markets with cash by buying billions in mortgage-backed securities and Treasury bonds each month.

But with the markets and American consumers acting as if the Covid pandemic is over, and with the Biden administration lobbying for another trillion dollars for infrastructure, the stage could be set for inflation beyond the Fed's control.

The White House did not immediately respond to CNBC's request for comment.

Good report card

By most economic metrics, U.S. workers and businesses have staged a robust recovery from the pandemic thanks in large part to an unprecedented policy response by both the Trump and Biden administrations.

The 46th president's critical priorities were on full display in the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Democrats ushered through Congress in March. The Biden relief bill not only authorized billions in additional funding for vaccine deployment, but also refreshed direct economic support in the form of $1,400 stimulus checks and an extension of enhanced jobless benefits.

Thus far, those programs appear to have worked to help the economy accelerate in the second quarter.

While total employment is still below pre-pandemic levels, U.S. employers have added back more than 2 million jobs since Biden took office and are expected to narrow that gap further in the coming months. Wages are up 2% over the last year.

The Labor Department's upcoming jobs report, due out Friday, is expected to show that employers added a strong 706,000 positions in June and that average hourly earnings rose 3.6% over the last year, according to economists polled by Dow Jones.

"A lot is going well. I think that the stimulus package really did its job. Trump had a good one, and then Biden had a good one," said Fundstrat Global Advisors policy analyst Tom Block. "The jobs numbers, while they haven't been as big as some would have liked, are pretty darn good. They're moving in the right direction."

Reports from corporate America are also upbeat.

With the first-quarter earnings season over, 86% of S&P 500 companies reported earnings results that were better than expected, the most in any quarter since at least 2008, when FactSet first began measuring.

The second quarter is already shaping up well for C-suite executives: A record-high number of S&P 500 companies have issued positive earnings and sales guidance for the three months ending June 30, according to FactSet earnings analyst John Butters.

The S&P 500, up a dizzying 14% in six months, closed at another record high on Tuesday.

The Atlanta Federal Reserve, which tracks data in real time to estimate changes in gross domestic product, expects GDP to grow at an 8.3% annualized pace for the second quarter.

Like any president, Biden hasn't been shy on sharing news about a hot economy.

"The bottom line is this: The Biden economic plan is working," the president said in late May. "We've had record job creation, we're seeing record economic growth, we're creating a new paradigm. One that rewards work — the working people in this nation, not just those at the top."

Cloudier skies ahead?

For all the fanfare a vigorous recovery merits, economists are starting to wonder whether the White House's most-recent stimulus efforts are a good idea.

Biden and a bipartisan group of senators announced last week that they had reached an agreement on a $1.2 trillion deal to fund improvements to roads, bridges, broadband and waterways. The Senate is expected to consider that bill in the coming weeks.

Meanwhile, the administration is also asking lawmakers to approve an additional $1.8 trillion in new spending and tax credits aimed toward children, students and families.

And that gives economist Sinai pause.

"The tail wind is now getting so big that nobody could say what it's going to bring," he said. Right now, "it's $5.9 trillion. Now, with probably a trillion of infrastructure, it's almost $7 trillion. That's 30% of GDP and has no historical precedent. And it could be too big."

Investors and economists have for weeks warned that rising input costs, while manageable over a prolonged period, are likely to be passed on to American consumers if businesses feel they can't absorb them without a material impact on earnings.

And evidence of that is already starting to trickle in.

The consumer price index jumped sharply this spring, and was up 5% year over year in May, the hottest pace since 2008. The core personal consumption expenditures price index, the Fed's preferred inflation gauge, rose 3.4% in May from a year ago to notch its fastest increase since the early 1990s.

While higher gasoline and grocery prices are annoying — the average price for a gallon of regular gasoline purchased by American consumers is up 92 cents over the last 12 months — accelerating inflation also draws the Fed's attention.

When the central bank feels that the economy is overheating and price growth is excessive, it raises interest rates and curbs asset purchases to help "pump the brakes." That sort of tapering has been known to depress equity markets since higher interest rates erode the value of future corporate earnings.

Persistent inflation or inflation expectations can also impact the economy in more direct ways.

Higher interest rates through Fed tightening mean fewer people are able to afford loans on cars or homes. Rapid inflation also makes any price — a wage, a home assessment, or the cost of a gallon of milk — far more volatile, and therefore difficult to value.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell has reiterated that, while he expects inflation to rise in 2021, it is likely to prove transient. Sinai isn't so sure.

"I don't think with this kind of growth and stimulus from the fiscal side that's coming into the economy anyone should be sanguine, or assume that inflation is a blip," he said. "History is very clear: Once an economy gets going, once the animal spirits get going and spending gets going, inflation, with a lag, follows."