Move over, Nefertiti! Queen Nefertari tells her story in “Queen Nefertari’s Egypt,” now on view at the Kimbell Art Museum through March 14.

This exhibition explores Egypt’s New Kingdom period (c. 1529 – 1075 B.C.) through the eyes of Nefertari, the celebrated wife of pharaoh Ramesses II.

“In general, this period represents the height of Egyptian civilization overall, just in terms of the power of Egypt, the culture and the artistry,” Jennifer Casler Price, the Fort Worth museum’s curator of Asian, African and Ancient American art, said.

Included in the exhibition are statues, jewelry, vases, papyrus manuscripts, carved steles, stone sarcophagi, painted wooden coffins and objects used by craftsmen to build the royal tombs, all drawn from the Museo Egizio in Turin, Italy.

Get DFW local news, weather forecasts and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC DFW newsletters.

Ramesses II, who reigned from 1279 – 1213 B.C., had eight wives. “Of those eight, Nefertari was his favorite,” Price said. “Her name meant ‘beautiful companion.’ She also was distinguished by the fact that she was literate. She could read and write hieroglyphs and that was unusual for women of the period.”

Her education made her an asset to her husband. “When Ramesses came to the throne, they embarked on a number of excursions around the kingdom,” Price said. “Nefertari went with him on these excursions and was able to get a bird’s eye view of the politics and diplomacy and the range of people of this vast empire. And we know later she kept up certain diplomatic correspondence.”

The Scene

Ramesses II was a great builder of monuments, tombs, and temples. He built a temple in honor of Nefertari, inscribed with “the one for whom the sun shines.”

“Ramesses thought she was so beautiful that the sun rose every day to illuminate her face and her beauty,” Price said. “She wasn’t just his favorite. She did play an important role during his time as pharaoh.”

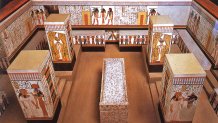

Until Ernesto Schiaparelli, an Italian archaeologist, discovered her tomb discovered in 1904, Nefertari was only known though depictions in Ramesses’ monuments. Although the tomb was looted, a few objects give some clues about her importance. The tomb is large, almost as large as a pharaoh’s tomb. Elaborate mural paintings describe the journey Nerfertari must take to reach the afterlife. A wooden model of the two-level tomb is on display in this exhibition and features the murals to scale.

Fragments of her pink granite sarcophagus lid, small wooden figures called shabtis and a faience amulet in the shape of a djed-pillar are also on display. Palm leaf sandals and a pair of mummified knees believed to be the queen’s only surviving remains reveal something about her physical appearance.

“The sandals are a women’s size nine, but the proportions of the knees indicate she was 5’5 or 5’6,” Price said. “It really begs the question of her background. Where did she come from?”

This exhibition gives perspective on the daily life of women in Egypt, specifically royal women living in the women’s palace. Women were active members of Egyptian society.

“In some senses, they actually had independence. They could own property, they could run businesses, they could stand up in a court of law. If they were getting a divorce, they could keep what they had,” Price said. “However, within that context, you still have a hierarchy even with the female population, especially looking at the women’s palace.”

Cosmetics were an important part of Egyptian life. “Both men and women wore make-up,” Price said. “Cosmetics served a medicinal purpose.”

Kohl was considered a disinfectant for the eyes and make-up was used to protect the face from Egypt’s harsh sun and wind. The exhibition includes a variety of cosmetic tools and perfume bottles.

Evidence of musical activity fills the exhibition.

“There’s a wonderful little case that has musical instruments. So, women could not go into the inner sanctum of the temple. That was the priests and the pharaoh,” Price said. “But women could participate in these religious ceremonies through music and dance. And music was an important part of their daily life in the palace.”

Another queen is highlighted in this exhibition: Ahmose-Nefertari. She and her son established Dier el-Medina, a village for the artisans working on the royal tombs. “Because they are in the employ of the royal family, they are of the highest level of skill and artistry,” Price said.

Schiaparelli also excavated Dier el-Medina, discovering the tools and everyday life objects of the artisans. Crockery as well as tools of the trade like hammers have been unearthed. “These things were held in the hands of these workers 3000 years ago,” Price said.

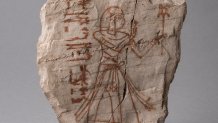

Schiaparelli discovered small fragments of limestone called ostraca. Artisans used these fragments like a sketchbook, practicing their drawings of gods, goddesses, animals, and barges. “These sketches are so fresh and immediate and again, you feel the hand of the artisan,” Price said.

Funerary steles the artisans created for themselves feature the village’s founding mother and son. “This village was presumably established by Ahmose-Nerfertari and her son and so consequently after their death, they became deified. They became the patron god and goddess of this artisan village,” Price said. “So that’s an instance of a queen being deified.”

The exhibition’s combination of objects reflects this extraordinary and mysterious chapter of Egypt’s history. “When you see those sandals, you step into the sandals of Nefertari and you try to imagine what it was like in Egypt,” Price said.

Learn more: https://www.kimbellart.org/