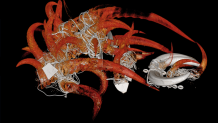

One of the most intriguing patients at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center is a fearsome-looking helmet mask from the Dallas Museum of Art’s collection. The museum’s Conservation and Arts of Africa departments collaborated with the medical center to learn more about the mask – inside and out. The komo mask and its CT scans make up the exhibition Not Visible to the Naked Eye: Inside a Senufo Helmet Mask, now on display on the Conservation Studio Landing through March 21, 2021.

This collaboration began with medical students touring the museum. The medical center was testing some new equipment and an object from the museum would be a perfect guinea pig. The West African mask was a strong candidate.

“There are many objects we would like to know about, but this one was particularly intriguing because there’s a lot going on with all of these attached horns and mirrors and cowrie shells and the encrustation. Is there anything in the horns? Is there anything we can’t see that we should know about?” Dr. Roslyn Walker, the museum’s Senior Curator of the Arts of Africa, the Americas and the Pacific and The Margaret McDermott Curator of African Art, said.

A member of the all-male Komo society would wear the mask at ceremonies and secrets events. The Komo society maintained social and spiritual harmony in Senufo villages in Côte d’Ivoire, Mali and Burkina Faso.

Beginning in 2016, the museum's Conservation Team began the in-depth investigation into the mask’s complex material composition with visual analysis and binocular microscopy, X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF), and Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)).

To further the research project and answer additional questions, UTSW was approached to assist with advanced imaging techniques. Dr. Matthew A. Lewis and Dr. Todd Soesbe, faculty members at the Department of Radiology at the Medical School of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, performed spectral imaging CT scan tests.

A team from the museum carefully prepared the mask for transport to the medical center and watched as it went through the CT scanning process. “It was just like putting a person in the machine,” Walker said.

For conservators at the museum dedicated to doing no harm to the objects they are studying, technology is the best way to fully investigate a complicated piece. “This was a wonderful way to study it in a non-invasive way,” Fran Baas, the museum’s Interim Chief Conservator, said.

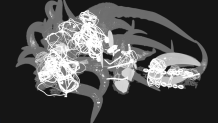

The spectral CT scan reveals details an x-ray cannot. “X-rays are one-dimensional. What’s nice about a cat scan is it’s like a loaf of bread. With a spectral CT, you can see it and it spins,” Baas said. “You can see internally and spin it. It’s not like one loaf of bread, one direction. It’s all the way through and three-dimensions and the best part is it is colored-coded. Depending on the density of the materials, it will show up in a different color.”

Things to Do in DFW

Things to do in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, from the arts and events to restaurants and bars.

The color-coding is particularly helpful to understand the female figurine nestled within the imposing horns. “Because the spectral cat scan shows things of different densities in different colors, she shows up as a different tone than the mask. She’s a different wood which is awesome to know,” Baas said.

The CT scans revealed how the mask is constructed and isolated other elements used in the mask: the wood structure, glass and wire. The museum has also learned more about the encrustation that gives the mask a uniform appearance. “It’s an amazing object. It’s nice to see how it is constructed through the cat scan,” Baas said.

With help from the Dallas Zoo and more detailed information from the CT scan, 33 of the 34 horns have been identified. “There are all wild animals. They are ferocious animals. They’ll kill you if they get a chance, so the mask is intentionally frightening,” Walker said. “Past experience with other cultures tells us that there was a reason for the choice. Part of it is that these were not domesticated. These were wild animals out in the forest. Each of those animals has a characteristic, a personality trait that is important to humans,” Walker said.

One of the most fascinating discoveries are skeletal remains of small lizard found within one of the horns. “They are sacrificial offerings that empower the object,” Walker said.

The more the museum learned about the mask, the more curators and conservators wanted to know, particularly about the objects in the mask. “Questions still have to be answered. That’s the fun part of what we do,” Walker said.

Complementing Not Visible to the Naked Eye: Inside a Senufo Helmet Mask is Wearable Raffia, an exhibition celebrating African textile design on museum’s third floor Textile Gallery. The exhibition features 15 works of art from the museum’s collection representing several groups across four African countries, including the Bamileke (Cameroon), Dida (Côte d’Ivoire), Kuba, Suku, and Teke (Democratic Republic of the Congo), and the Merina (Madagascar).

Skirts, headwear and a shawl demonstrate how tree bark and leaves were harvested for fiber before cotton fibers were imported. “Raffia clothing, shoes, and accessories are currently in vogue in the USA and Europe. Since the early 2000s, such Western fashion houses as The House of Dior, Paris, have commissioned raffia fabrics from weavers in Madagascar. In Africa, weavers have been transforming raw raffia into clothing and headwear for centuries,” Walker said. “This visually appealing exhibition, which includes a ‘please touch’ section, reveals the meticulous craftsmanship, imaginative designs, and ways to wear raffia cloth in Africa.”

Learn more: www.dma.org