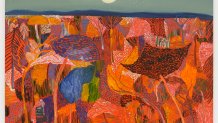

Matthew Wong’s career was like a shooting star: fleeting and spectacular. “Matthew Wong: The Realm of Appearances” at the Dallas Museum of Art chronicles Wong’s six-year career and is the late artist’s first museum retrospective, now on view through Feb. 19.

Born in Toronto, Wong earned his undergraduate degree at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and went to Hong Kong to earn a MA in photography from the City University of Hong Kong’s School of Creative Media. Wong was diagnosed with autism and Tourette syndrome and dealt with depression throughout his life. He died by suicide at age 35 on October 2, 2019. Wong’s art reflects his sense of confidence.

“There was so much that he couldn’t control of his own body, but in painting, he found so much freedom and he could control that. He knew was very good at it,” said Dr. Vivian Li, the museum’s Lupe Murchison Curator of Contemporary Art and the curator of this exhibition.

Get DFW local news, weather forecasts and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC DFW newsletters.

The exhibition features approximately 50 paintings and is organized chronologically, beginning in 2013. Wong had turned away from photography, disillusioned by its mechanical nature. Once he began painting, he became prolific.

“He was rapidly accelerating his development, experimenting constantly. He was painting at least a painting a day, if not more,” Li said.

His early works feature human figures prominently.

Local

The latest news from around North Texas.

“In his early works and I think throughout the exhibition, I think that one theme is him trying to find his own place in the world,” Li said.

Wong was a self-taught painter and he boldly combined paint and ink, even using ink to create negative space.

“If you were actually trained as an ink painter, you would not see this inkiness,” Li said.

Landscapes became Wong’s preferred genre because he could easily experiment with various painting styles and explore many emotional planes.

“In many ways, he was very interested in the interior landscape that he could explore through the landscape genre,” Li said.

While in Hong Kong, he wrote poetry, sharing his poems at open-mike readings. A Poet’s World references Wong’s other artistic outlet.

“He actually very rarely wrote on the paintings themselves but here, he wrote in Chinese,” Li said. “It’s kind of mimicking the Chinese landscape tradition of inscription.”

Poetry and painting expressed his artistic goals.

“He saw poetry and painting as both bypassing the logic of language and getting to the sensations and associations, and that’s what he was trying to achieve in his paintings,” Li said

When he returned to North America in 2016, he visited friends in New York, Los Angeles and Michigan. His work was displayed in an exhibition called “Outside.” The exhibition featured landscapes and artists who were not traditionally trained. The DMA exhibition includes two works displayed at “Outside.”

“It’s a pivotal moment in Matthew’s career,” Li said.

In a matter of only a couple of years, Wong’s style was changing rapidly. He continued to paint multiple works a day, watched a movie a day, loved hip hop, and stopped for a piece of cheesecake at a favorite café while on long evening walks. He developed friendships with other contemporary artists through social media and studied the masters online and through museum visits.

The influences burst onto his canvases, creating evocative landscapes featuring broad brushstrokes, vibrant colors, and impossible patterns of dots. His works openly referenced Post-Impressionists, Fauvists, 17th-century Qing period ink painters and contemporary artists he respected and championed. In contrast to his early works, the human figure becomes smaller, almost dwarfed by the landscape.

“The landscape is becoming more central to the subject,” Li said.

Because he was so prolific, Wong often reused canvases. The DMA Paintings Conservator Laura Eva Hartman studied these reused canvases, discovering two or three paintings layered on top of each other on one canvas.

“It wasn’t that he would touch-up works. His mode of painting or his approach to painting was that it had to be of the moment. Then he could not return to it. The moment was gone,” Li said.

The exhibition also features The West, a work the Dallas Museum of Art acquired in 2017 at the Dallas Art Fair. It was the first work of his that had been acquired by a museum.

“He was grateful to have this institutional recognition,” said Li.

Wong came to Dallas for the Dallas Art Fair and watched as The West was uncrated. He had finished the work earlier that year, but upon seeing it at the fair, he decided the constellation of stars was not impressive enough. He quickly went to work, painting in the booth as representatives from the museums arrived at the fair.

“It came to the museum wet,” Li said.

During the last two years of his life, Wong continued to push himself to grow.

“He wanted to continue to experiment. He did not want to settle into ‘this is my painting.’ He was striving to continuously develop himself, so he was starting to slow down,” Li said.

He began experimenting with monochrome, specifically interested in blue.

“His last series of paintings were devoted to the color blue with the emotional and psychological depth one color can have,” Li said.

Wong’s last works do not reflect melancholy. Instead, Landscape with Ella, painted from a snapshot a friend sent to Wong via text, shows a transient, intimate moment. Painted in the last year of his life, See You On the Other Side is the culmination of Wong’s artistic development with an unpainted white expanse at the center of a majestic landscape.

And in a flash, Wong’s shooting star vanished.

Learn more: Dallas Museum of Art

*This exhibition acknowledges Wong's mental health struggles with a pamphlet highlighting mental health resources. If you or someone you know is struggling, 988 is the three-digit dialing code for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, providing free and confidential 24/7 support.